He was the “boy-king” who became a household name 3000 years after his death. But is there any truth in the rumours of the pharaoh’s curse?

The discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1922 is one of the most important archaeological finds in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings — bringing international fame to Howard Carter, the British archaeologist who dedicated his life to the search for the tomb of the “boy-king”.

His extraordinary find catapulted Carter into international fame. But some believe he paid a huge price for his success — being struck by the so-called “curse of Tutankhamen” that also killed Lord Carnarvon, the man who bankrolled the search and several others who visited the tomb. (If you’re not willing to buy the ‘curse theory’ there’s always the less-fascinating explanations involving mosquito-borne illness, cancer, murder and suicide).

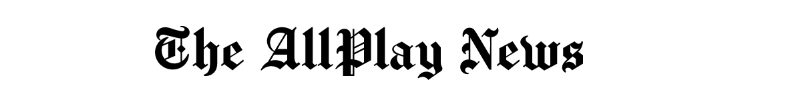

While Carter’s research team first located King Tut’s tomb in 1922, it wasn’t until January 4, 1923 that the most important discovery of all was made — the Egyptian pharaoh’s sarcophagus, which contained a solid gold coffin of the pharaoh’s remains.

Carter’s discovery astounded the world; a treasure trove of magnificence, from chariots, chairs and caskets to the great shrine of the boy-king who was also known as the “Lord of the West”.

For three thousand years, much of the tomb was hidden from grave robbers.

Ninety-five years later, the story of the search for the tomb and the legend of King Tut’s curse is as captivating as ever.

The painstaking search for the tomb

Howard Carter started searching for the tomb of the little-known pharaoh in 1891 but he was forced to abandon his project in 1914 as World War 1 broke out.

Then, as the war died down, Carter resumed his search, even though many archaeologists believed he was wasting his time. Surely, there was nothing left in the Valley of the Kings to discover?

Carter saw the tomb of King Tut as the find that would make his career, even though he was an obscure pharaoh whose name was only ever uttered among academics.

There had already been several excavations throughout the valley in the late 1800s, uncovering the tombs of almost every known pharaoh.

However, the resting place of Tutankhamun was still unaccounted for and Carter refused to let go of his strong feeling that the Valley had one more secret to reveal.

King Tut the teenage king

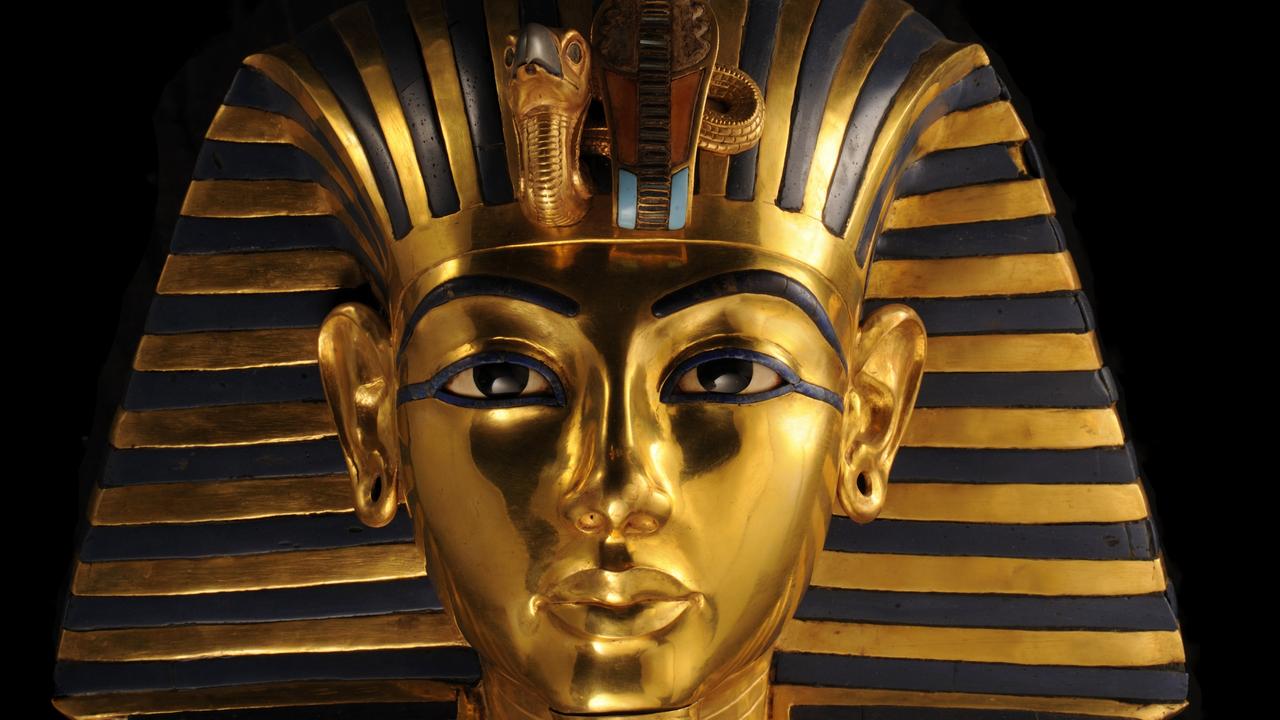

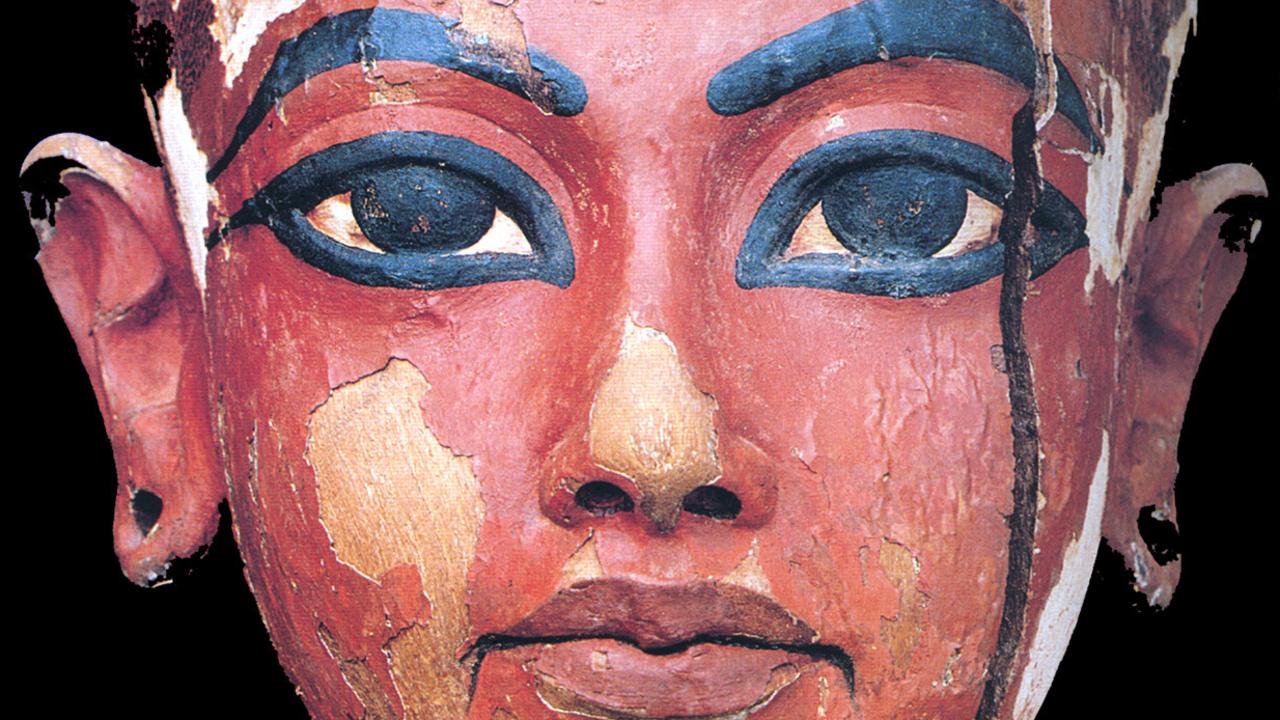

Tutankhamen (1332-23BC) was only 18 when he died and, even though historians don’t believe he achieved anything of note during his short reign, he is the most famous pharaoh in history, thanks to Carter’s incredible discovery.

It was King Tut’s father, Amenhotep IV, who was arguably a more impressive pharaoh — he was the first ever monotheist when he decided to end the ancient Egyptian tradition of worshipping multiple Gods.

Instead, he settled for just one, known as Aten (the Sun).

Historians have debated for decades as to how King Tutankhamun died.

Signs of damage to his skull led to a theory that a rival to the throne might have murdered him. Others believe the archaeologists did the damage themselves by mishandling the royal remains.

Tests have shown evidence of malaria, as well as a broken leg. Some of the more bizarre theories revolve around the idea that King Tut was bitten by a hippo or that he died in a chariot race.

Evidence that the pharaoh had a club foot and cleft palate led some historians to theorise that he might have been the product of inbreeding.

But a “virtual autopsy” carried out by Italian scientists in 2014 showed he most likely died from an inherited illness.

Valley of the Kings

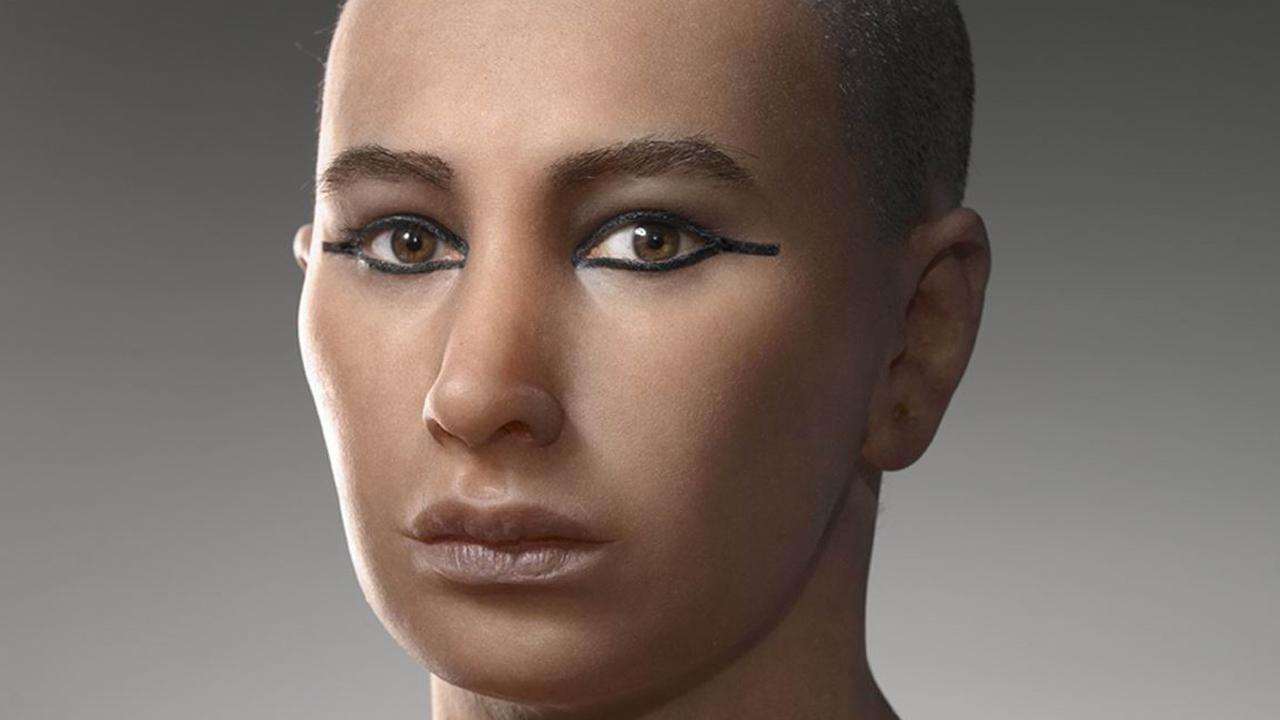

Egyptian royalty were traditionally buried in the Valley of the Kings between 1539-1075 BC. It’s a desolate area, a short distance from what was once the ancient city of Thebes, which is known today as Luxor.

There’s no shortage of tourists visiting the Valley today — this journalist was among those wandering the tombs in the late 90s (shortly before the Luxor massacre of 70 tourists in 1997.

It is a wasteland of sand and rocks, with no vegetation, and absolutely no shelter from the relentless Egyptian sun.

It was said to be the perfect place to bury royalty because, surely, no grave robbers would dare to pillage the burial vaults in a land surrounded by death, even if the tombs were filled with gold and treasures fit to accommodate a Pharaoh’s trip to the netherworld.

In his book, the Tomb of Tutankhamen, Carter wrote that, as his search continued, the discovery of artefacts such as a piece of gold foil, and other items bearing the name of Tutankhamun gave him hope that his tomb had still not been found.

He also believed the locations of these items was a definite clue to the area where he must search, as he continued to excavate right down to the bedrock.

Carter’s financial backer, Lord Carnarvon, was tempted to call off the search for the tomb after six years of work led to absolutely nothing.

But Carter convinced him to allow him to search the Valley for one more season.

It was a decision that resulted in the 20th century’s most incredible discovery.

The discovery of the tomb

Carter was well aware that 1922 was the last year he was able to search for the tomb — beyond that, he wouldn’t be able to finance the project.

But then, a miracle. On November 26, Carter’s Egyptian labourers stumbled upon a series of steps leading down to a sealed door.

Taking hours to clear debris from the door, the men eventually saw the top of a door, sealed with plaster. Could this be the doorway to the young King’s tomb?

When Carter spotted the undisturbed seals of the royal necropolis, his heart raced with excitement.

He immediately had the staircase filled in (to prevent others from finding it) and sent a telegram to Lord Carnarvon: “At last have made wonderful discovery in valley; a magnificent tomb with seals intact.”

Carnarvon rushed to Luxor to witness the opening of the tomb. It was a very slow process as the men carefully drilled a small hole in the top corner of the doorway.

That’s when Carter noticed that tomb robbers had dug a hole through a section of the passageway. There were further signs that another hole had been made in the doorway and resealed. So, the tomb had most likely been robbed twice.

Then, Carter placed a candle inside the small opening.

Carter wrote: “With trembling hands I made a tiny breach in the upper left hand corner. Darkness and blank space, as far as an iron testing-rod could reach, showed that whatever lay beyond was empty, and not filled like the passage we had just cleared. Candle tests were applied as a precaution against possible foul gases, and then, widening the hole a little, I inserted the candle and peered in.”

What happened next has become one of the most memorable exchanges in the history of archaeology.

Carter wrote: “For the moment — an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by — I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand in suspense any longer, inquired anxiously ‘Can you see anything?’, it was all I could do to get out the words ‘Yes, wonderful things’.”

The “wonderful things” Carter was gazing at was a room filled with magnificent items, “strange animals, statues and gold; everywhere the glint of gold,” as he later wrote.

This was the greatest collection of Egyptian antiquities ever discovered. But this was just a small section of the tomb — beyond this room was another antechamber filled with more incredible treasures.

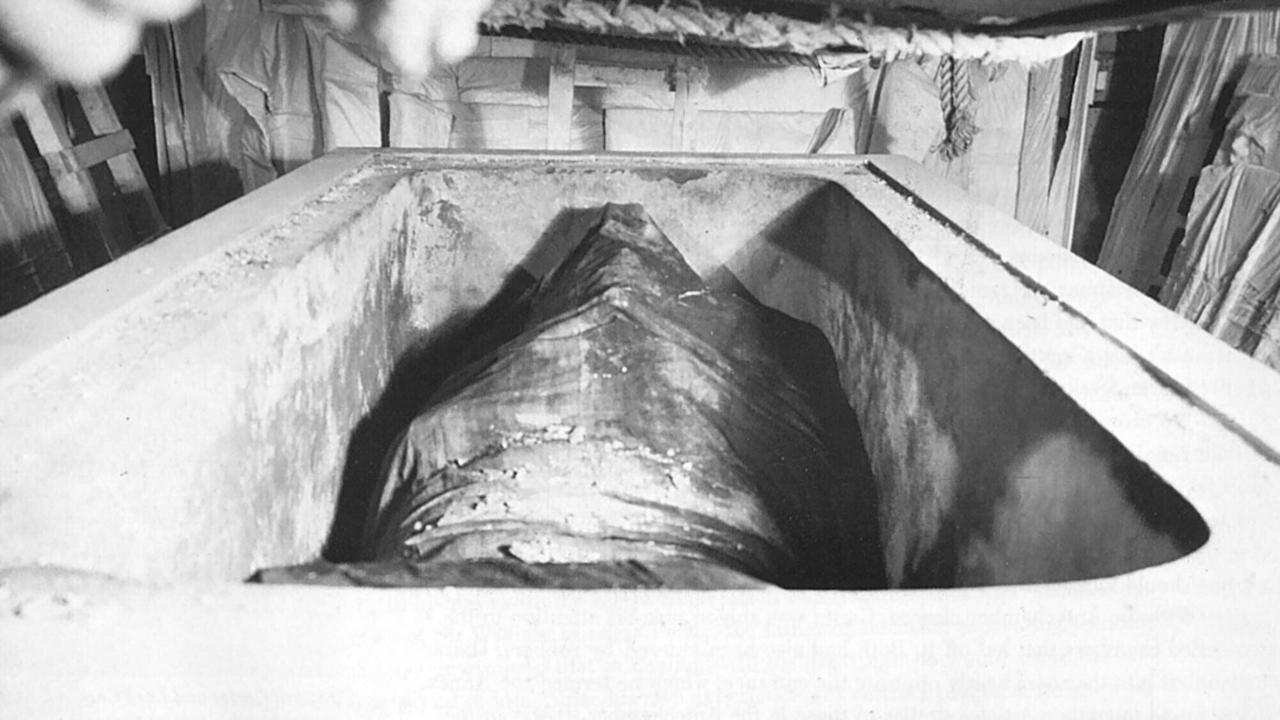

It took months for the team to photograph and catalogue every single item. Then in January 1923, Carter began to break through another sealed door where he was hoping to find King Tut’s sarcophagus.

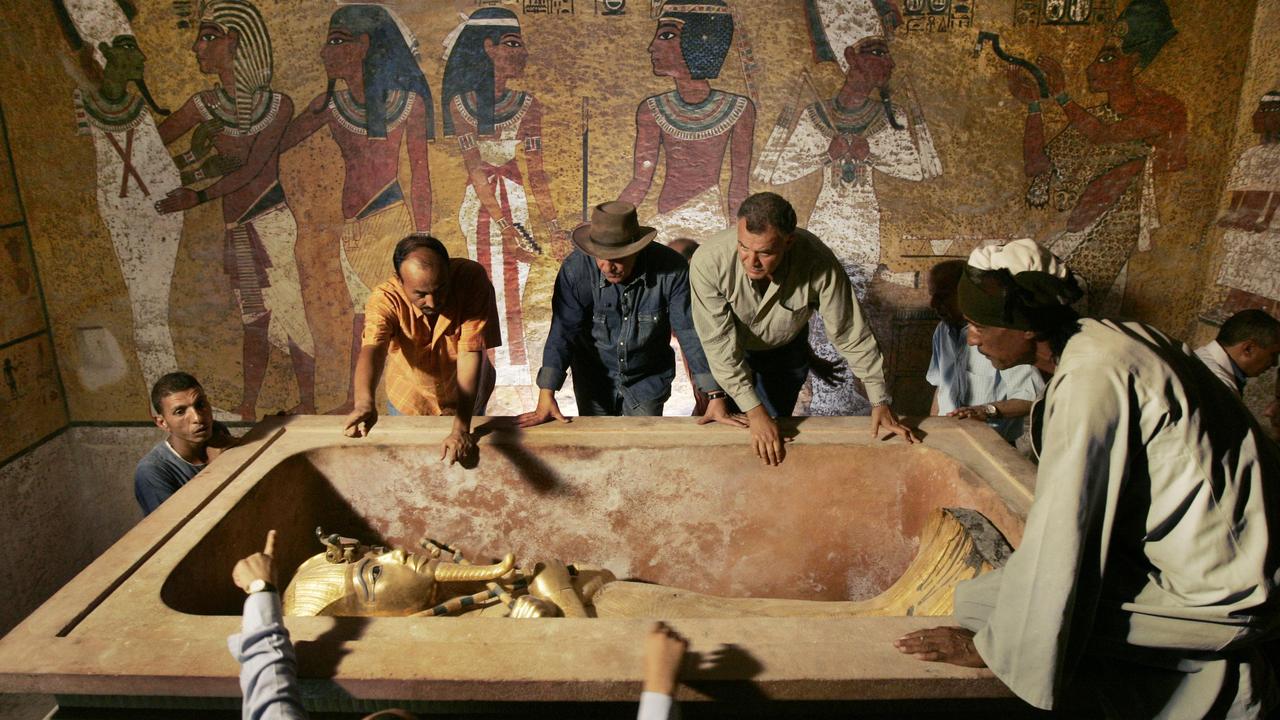

The Burial Chamber featured a large shrine, with walls made of gilt wood with a bright blue porcelain. As Carter and his team disassembled the shrine, they found four shrines in total, with the final shrine containing the sarcophagus, which was yellow and made from a single block of quartzite. When the men lifted the lid, a gilt wooden coffin was revealed, distinctly human shaped. Lifting the lid of the coffin, they found another coffin, made entirely of gold.

At long last, the royal mummy of Tutankhamun was unveiled, 3000 years since his burial. The find propelled Carter into the international spotlight, with many debating whether or not his find was a stroke of luck.

Yale University Egyptologist John Darnell claims luck had little to do with the discovery and Carter was meticulous in the methods he applied during his search.

“Carter found the tomb in a methodical way. He did all the necessary background work. He didn’t simply look for the door of a tomb, but rather he went at it in a way that we would probably characterise today as a form of landscape archaeology,” Darnell said.

“Carter really worked himself into the lives of ancient Egyptian necropolis workmen. He knew the hills, he knew the paths, he knew what happened when rainstorms hit the area.”

The curse of King Tut

For the superstitious among us, there’s long been a belief that anyone that breaks into a pharaoh’s tomb will be struck by an ancient death curse.

This curse, which apparently applies regardless of whether you’re a thief or an archaeologist, will manifest itself in the form of illness, death or, if you’re lucky, just bad fortune.

Stories about the curse came to light when several members of Carter’s team, as well as other visitors to the tomb, died in “mysterious circumstances” that actually weren’t terribly mysterious at all.

Firstly, Lord Carnarvon died on April 5, 1923, shortly after a mosquito bite which led to an infection. His death sparked a media frenzy, with headlines reporting “death by King Tut curse”.

Other deaths included a radiologist who X-rayed King Tut’s remains, a member of Carter’s excavation team (who died of arsenic poisoning) and a visitor to the tomb who developed a fever shortly after his visit.

Carter’s personal secretary was murdered, Carnarvon’s half-brother died of malaria and Carter’s secretary’s father jumped off a building.

And, even though Carter died a decade after discovering King Tut’s tomb, his death is still attributed to “the curse”.

Why? Because it’s a juicier story than what really killed him: lymphoma.