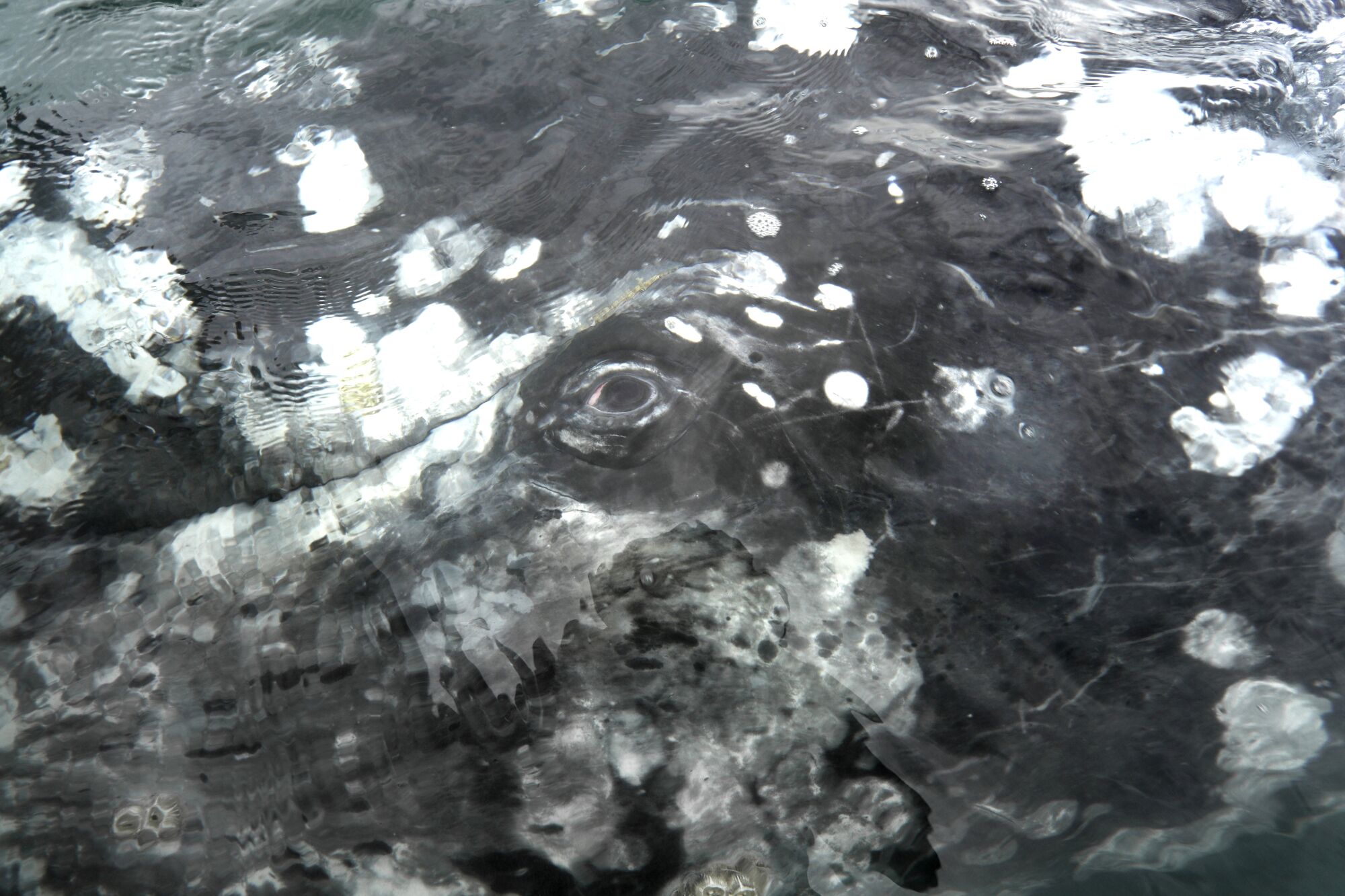

March 2020 photo of a gray whale surfacing with open eyes in Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California.

When gray whales began washing up dead in large numbers in 2019, many scientists hoped it was just a short-term phenomenon, and that the leviathans would quickly recover and rebound.

But three years later, the die-off continues for gray whales living and migrating along North America’s Pacific coast.

The population is down almost 40% from its peak in 2016. And in a report released Friday, federal scientists said the number of calves born last year was the lowest they’ve seen since they started observations in 1994.

“Given the continuing decline in numbers since [the peak in] 2016, we need to be closely monitoring the population to help understand what may be driving the trend,” said David Weller, director of the Marine Mammal and Turtle Division at NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center, in a statement. “We have observed the population changing over time, and we want to stay on top of that.”

In 2019, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declared an “unusual mortality event” after an alarming number of gray whales began washing up along the shore from Mexico to Alaska. Then and now, the cause of the die-off remains elusive, but it appears that something has drastically altered the food web of these large, bottom-feeding cetaceans.

Every year, gray whales migrate from the warm, protected lagoons of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula to the cold waters of the Arctic and sub-Arctic, where they feed for months on small, shrimp-like creatures that dwell in the mud. Then they return to Mexico, where they mate, give birth and nurse their calves.

A gray whale pushes her calf to the surface in Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California.

It’s a 12,000-mile round trip migration that leads the whales past North America’s busy coast line — through shipping lanes, around fishing vessels, near crowded and intrusive tourist boats and occasionally into the maws of hungry orcas.

Gray whales have had population contractions in the past. Between 1999 and 2000, the population declined by about 25%. However, it quickly rebounded, peaking in 2015-2016.

Researchers pointed to unusually cold temperatures as a likely cause of that contraction. The frigid temperatures during that period expanded the reach of Arctic sea ice making it difficult for the whales to access their traditional prey items of amphipods and other shrimp-like creatures on the ocean floor of the Chukchi, Northern Bering and Beaufort Seas.

Two gray whales feed in the sediment not far from Pasagshak Bay off of Kodiak Island, Kodiak, Alaska.

This time, scientists say there are likely multiple causes, including a prolonged period of warm temperatures — a consequence of climate change — a loss of sea ice and the subsequent movement and changes in the whales’ prey items.

Many of the whales they encounter and observe appear skinny, and the bulk of whales that have stranded since 2019 — roughly 600 — have been malnourished.

However, that’s not the case for all of the whales. Some were clearly killed by ship strikes, or drowned after being entangled in fishing line and nets, or shredded and eaten by orcas. Others may have died of disease.

“There is no one thing that we can point to that explains all of the strandings,” said Deborah Fauquier, Veterinary Medical Officer in NOAA Fisheries’ Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program. “There appears to be multiple factors that we are still working to understand.”

And the mothers that are having calves seem to be healthy and adequately fed, said Aimee Lang, a fisheries biologist with NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center who leads the field teams that count the whales as they migrate.

While population counts for gray whales are typically conducted over the course of a two-year period, this year NOAA is adding a third year. Observers will watch from points along California’s central coast — at Granite Point for the southward migration and Piedras Blancas for the northward.

Lang said they work in teams of two and watch for whales as they swim by; they also send drones out to capture data regarding their size and health.

Elsewhere, whale watchers have noticed gray whales exhibiting unusual feeding behaviors, including this past summer in San Francisco Bay where the Marine Mammal Center’s Tim Markowitz and others saw gray whales lunge feeding — a behavior typical for humpbacks, in which they open their jaws wide, and lunge across the water’s surface scooping up fish and krill.

“When I heard they were doing that, I figured the stories were wrong. It must have been humpbacks, “ said Markowitz in a July interview about a bonanza of anchovy in the Bay. “But then I saw it, and I was like ‘whoa!’ Gray whales don’t do that.”

Elsewhere, gray whales have been observed feeding in areas they have historically avoided, including the shallow lagoons of the Baja Peninsula and the muddy, sandy shores of San Francisco Bay and Long Beach Harbor.

A whale-watching group gets a closeup view of a gray whale in Laguna San Ignacio.

Gray whales have been called the “jeeps” of the ocean, because of their opportunistic feeding habits (although they prefer foods that live on the ocean floor, they will eat krill and other critters in the water column and on the surface). They’ve also been called the “sentinels” — because if something starts happening to them, it’s likely you’ll see it elsewhere.

And that’s what has so many worried — if gray whales are having a hard time, a lot of others are, as well.

“What we hope to see in the next few years is that the abundance stabilizes and then starts to show signs of increase,” said Lang. “We will be watching closely.”

In May 2021, three gray whales washed ashore in the San Francisco Bay Area, where visitors to Muir Beach look at a decomposing gray whale.