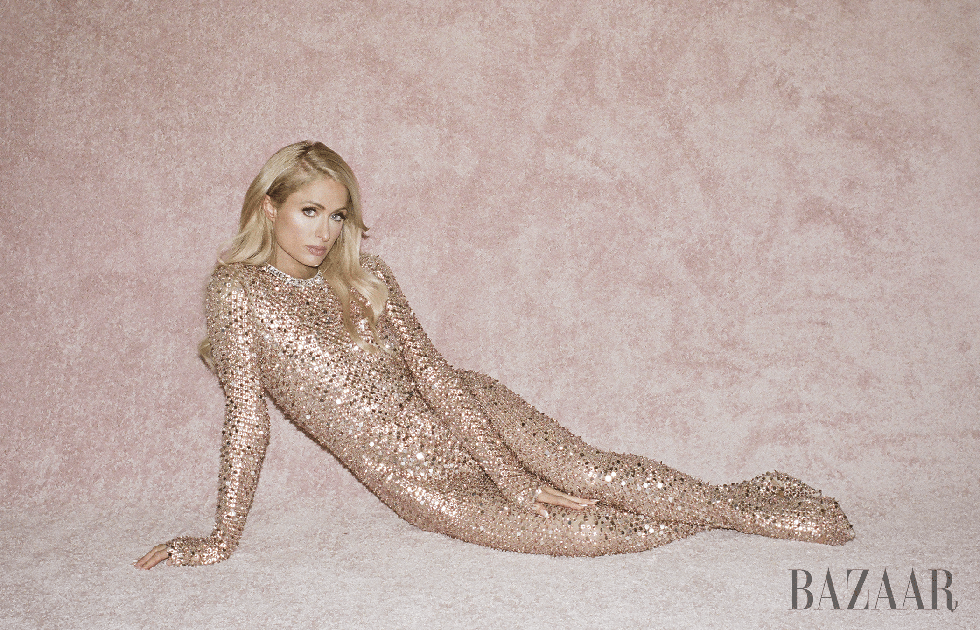

She created our century’s model of celebrity, but with a new memoir, a new baby, and a new perspective on life, Paris Hilton is reinventing herself.

On the day her son was born, Paris Hilton put on a brunette wig and a hoodie and checked into a hospital under a different name. Her platinum-blond hair is one of her many calling cards, and it felt imperative that she go unnoticed. Her baby’s impending existence was, at that point, a secret to the rest of the world, known only to Hilton, her husband, Carter Reum, and their surrogate. Even their immediate families would not find out until just before she announced his arrival on Instagram.

“My entire life has been so public,” Hilton says over the phone in late January, hovering outside of the baby’s nursery and speaking quietly while he naps. “I’ve never had anything for myself. We decided that we wanted to have this whole experience to ourselves.”

Once he’d been cleared to leave the hospital, she and Reum brought their son home, to the house they recently bought in Beverly Hills. For two full days, they were truly alone (they’d told their staff the house was being painted), enjoying the relative quiet of life with a newborn—getting used to his sleeping and feeding schedules and singing him lullabies. (Hilton was partial to “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” as well as her 2006 hit, “Stars Are Blind.” “The acoustic version,” she clarifies.) Then, when it seemed like the news was about to come out on its own, they broke the spell and announced they’d become parents.

Even with a surrogate, a pregnancy is a big secret to keep. But Hilton is used to keeping parts of her life hidden. In the 2020 documentary This Is Paris, she came forward for the first time about the abuse she suffered in her adolescence, after her parents, Rick and Kathy Hilton, shipped her off to a series of boarding schools that promised to reform troubled teens. She has since become a prominent advocate for shutting down the so-called troubled-teen industry; in 2021, she supported a bill to further regulate the schools in Utah, and she is now pushing for federal reform.

“All the NEGATIVE, HORRIBLE WORDS that they would say to me EVERY SINGLE DAY, that sticks with you. I just was not secure.”

It was the start of a transformative three years for Hilton. The entrepreneur, reality-television star, DJ, performer, perfumer, model, and socialite helped invent a certain kind of vacuous fame in the early aughts, when she was mostly famous for her last name, going to parties, being hot, and saying “That’s hot,” but at 42, the endlessly iterative star has traded playing Paris qua Paris for a more authentic, transparent version of herself. Her memoir, Paris: The Memoir, out this month, puts Hilton squarely in charge of her own cultural recontextualization—“How do we not see that the treatment of It Girls translates to the treatment of all girls in our culture?” she writes at one point, sounding Elle Woodsian—and plunges into darker, shocking details from her high school years. It’s the final step in her unburdening and all of the attendant change that has come with it, including marriage, motherhood, and a fundamental shift in her priorities. “Advocacy,” she writes in Paris, “saved my life.”

Hilton’s own childhood ended abruptly, violently. One could understand why she’d want to ensure her son’s welcome into this world felt sacred and safe. “I want to protect him and to be with him every second,” she says. “You have this mother instinct that kicks in, which I’ve never had before. I feel so complete now.”

It’s well documented that Hilton has two distinct voices. One is her regular, private speaking voice, which is low toned and almost sonorous; the other is the voice she uses for the public-facing character of Paris Hilton, which is higher pitched and coquettish, the real-life Valley Girl standard. In a mid-2000s clip that went viral on TikTok, where Hilton has flourished thanks to a new Gen Z fan base, Hilton bellows to the driver of a waiting car to wait “two minutes.” When an awaiting paparazzo asks how she’s doing, she transforms midstep: “Goooood,” she purrs.

In Paris, Hilton describes the character as “my steel-plated armor,” a “dumb blonde with a sweet but sassy edge”: “I made sure I never had a quiet moment to figure out who I was without her. I was afraid of that moment because I didn’t know what I’d find.” Dropping the act would mean navigating, and overseeing, yet another public reconstruction of herself.

When Hilton agreed to participate in This Is Paris, she didn’t anticipate that it would touch on her high school experience at all. But during filming, she and the director, Alexandra Haggiag Dean, grew close, and Hilton started to open up to her about what she’d been through. She was terrified before it premiered in September 2020, unsure of how her audience would react. “My brand had been so the opposite of that. I had this whole Barbie-doll, airhead”—and here she instinctively slips into the voice, as she does occasionally throughout our conversation—“ ‘perfect life’ persona. And there was some deep trauma that led to all of that.”

It’s early December, and we’re tucked away in a corner room in her home, with French doors that open out onto a sprawling backyard with a pool. Hilton is tired and cramping because she has spent yet another morning at her fertility clinic, where she completed her seventh egg retrieval to date. (Hilton and Reum, a venture capitalist, would like to continue expanding their family; she says she’s determined to have a daughter one day.) On the coffee table between us, someone has laid out a middle-school sleepover dreamscape—more bowls of snacks than a Cold Stone toppings spread, as well as a massive pitcher of lemonade—and she picks at sliced fruit as her two Pomeranians, Ether Reum and Crypto Hilton, yap like parakeets on the floor. (“They were named at the top of the market,” Reum tells me apologetically. “We’re thinking about Web3 names now.”)

Hilton and Reum are still moving in, but their interior decorator has started to hang art. Most of it is Paris-themed. In the sitting room where we talk, there’s a massive black-and-white portrait of Hilton; there’s also, in equal stature, one of Marilyn Monroe.

“I had this whole BARBIE-DOLL, AIRHEAD, ‘PERFECT LIFE’ PERSONA. And there was some deep trauma that led to all of that.”

“She was really misunderstood,” Hilton says, cross-legged on a white overstuffed couch in a black velour tracksuit and rainbow socks. She read Monroe’s memoir, My Story, when she was working on her own book and found she related to it so much that it made her cry. “She had horrible things happen to her, and she kept that all hidden and portrayed this fantasy life. And I definitely did that as a coping mechanism for all the trauma I went through. I didn’t even know who I was.”

When Hilton was 15, she moved into a Waldorf Astoria condo with her parents and three younger siblings (sister Nicky and brothers Conrad and Barron) in Manhattan. She started going to clubs and—not helped by her as-yet-undiagnosed ADHD—falling behind in her studies. She was kicked out of two elite Manhattan private schools.

“I was not a bad kid,” Hilton says. “I snuck out at night, got bad grades, ditched school. But my mom and dad were so strict. They wanted me to be home at 11:00.”

Hilton wanted to focus on her modeling career, but Kathy, a former child actor, didn’t want her to rush into the business. When she was 16, Kathy and Rick decided to send her to a for-profit behavior-modification program that had come highly recommended.

“She was breaking all of the rules,” Nicky remembers. “My parents had no idea what to do. They were trying to protect her.”

It happened overnight. Hilton remembers being woken up by two strange men who took her, screaming, from the apartment while her parents looked on in tears from their bedroom door. She was thrown into a waiting SUV and flown across the country with little explanation. For close to two years, Hilton was shuffled through a series of residential “treatment centers” across the country.

At CEDU, a now-shuttered “therapeutic boarding school” in California that Hilton attended, students were forced to participate in “attack therapy” or “raps,” long, combative group sessions in which they were encouraged to insult and denigrate one another for the bad behavior that had landed them there.

After CEDU, Hilton was sent to other similar programs and attempted to escape them with an admirable doggedness—her penchant for climbing fences, it turns out, is not just a party trick—but she was always found, sometimes with her family’s assistance, and brought back. At one school, she was once slapped and strangled in front of other students. Her fourth and final stop was Provo Canyon School (PCS) in Utah, which she has described as a total-lockdown facility. She was not permitted outside for 11 months. At one point, she stopped taking the pills she was given and was sent to a tiny solitary-confinement cell, called “Obs”—short for observation—as punishment.

“It’s a cold room,” Hilton recalls. “There’s blood on the walls and just a drain in the middle of the room. I had no idea what time it was; there’s no clock. You’re just going crazy.” She passed the time envisioning how she wanted to spend the rest of her life: “I started thinking, ‘What am I going to do when I get out of here? I am going to work so hard and become so successful that my parents, these people, a man—no one will ever tell me what to do again.’ I really equated money to freedom, independence, and happiness. That became my laser-beam focus.”

“Would I make the same choices again, knowing what I know now? Of course not!”

(In February of 2021, Hilton detailed these allegations of abuse she’d suffered at CEDU, Provo, and other schools before a state-senate committee hearing at the Utah capitol. When reached for comment, Provo Canyon School’s current CEO provided a statement noting that “Provo Canyon School was sold by its previous ownership in August 2000. We therefore cannot comment on the operations or student experience prior to that time. … We do not condone or promote any form of abuse.” Bazaar’s attempt to obtain comment from former representatives at CEDU, which shut down in 2005, was unsuccessful.)

Hilton’s parents finally pulled her from PCS in January of 1999, just a few weeks shy of her 18th birthday. “It was this whole new world,” she says. “I had not seen a TV. I had not seen a magazine. I had no idea what was happening in pop culture.”

Nearly 25 years later, Hilton says she’s forgiven her parents for sending her away. (Nicky says she didn’t know just how bad it had been until she watched the documentary; in it, Kathy learns for the first time about the conditions that Paris experienced. “Had I known this, Dad and I would have been there in one second,” she says.) Kathy apologized to her before her wedding. Hilton says she felt like she’d lost “the most important, most fun years of being a teenage girl. Sixteen to 18 is like …” She trails off, unable to call to mind something as typical as the prom or a graduation ceremony.

When Hilton got back to New York, she felt desperate to make up for lost time. She got modeling jobs, and she and Nicky started going to fashion shows and movie premieres. She learned quickly how to use the growing hordes of paparazzi who followed her around New York and L.A. to her advantage, gamely posing for high-value candid shots that were likely to land her in the tabloids and inventing a new kind of fame. “I had no agent, no publicist, no stylist,” she says. “I had a fake email address and would pretend to be my [own] manager.”

“I remember walking out with my sister and having 50 photographers screaming my name,” Hilton says. “I was like, ‘Oh, this is what love is.’ ”

She dressed herself with a nose for early-aughts excess: Barbie pinks, convertible roller-skate sneakers, Juicy Couture tracksuits—a kind of pure and youthful style experimentation that now seems old-fashioned. “All of that was just from us out shopping,” Nicky says. “Stylists have taken all the originality out of the game. It was so different back then. It was so real.”

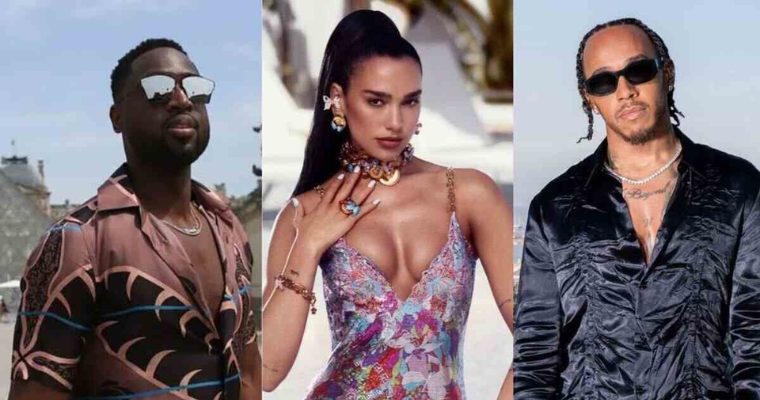

At the time, no one would’ve called the looks timeless, but the Y2K style Hilton helped popularize—low-rise jeans and going-out tops—has come back around. In September, she closed Versace’s Spring 2023 show in a hot-pink metal-mesh minidress. Nicky says one thing she loves about her sister, though, is that she “does not care about designers or trends at all.”

“She was just invited to the Celine show. She’s like, ‘What’s Celine?’ ” Nicky says, laughing. “She just wears what she wants, and I think it’s no mistake that she is the creator of some of the most iconic fashion moments of my generation.”

Hilton’s breakthrough moment came in December 2003, when The Simple Life—her wildly popular Fox reality show with childhood friend Nicole Richie—premiered to 13 million viewers. “That’s when the character really came out, because the producers wanted Nicole to be the troublemaker and [me to] be the airhead,” Hilton says. “Everyone assumed that’s who I was in real life.”

The show catapulted Hilton into a new category of fame—and the scrutiny that came with it. It was generally an unkind era for young women stars, but the distaste for Hilton was an especially potent brew: She was a hotel heiress with a famous last name, no discernible talent, vocal fry, and a thousand-yard stare. The reception to her could be distinctly vicious. Nicky, who has always had a protective instinct toward her big sister, remembers sneaking out of the Waldorf apartment to flip over newspapers in the hallway so that their parents wouldn’t see headlines about Paris.

“I really equated MONEY TO FREEDOM, INDEPENDENCE, and HAPPINESS. That became my laser-beam focus.”

In 2007, Hilton’s party-girl era came to a crashing halt when she was sentenced to 45 days in an L.A. County jail for a probation violation related to a reckless-driving charge. She attended the MTV Movie Awards the same night she was processed, and comedian Sarah Silverman told the crowd, “Paris Hilton is going to jail.” Everyone cheered. “I heard that to make her feel, like, more comfortable in prison, the guards are going to paint the bars to look like penises,” Silverman added as the camera flashed to a noticeably uncomfortable Hilton. (Silverman has since apologized.) A few months later, after she’d served her time (she was released after 23 days for good behavior), Hilton appeared on Late Show With David Letterman and sat through nearly five minutes of gleeful grilling about her stint in jail. She begged him to stop and cried as she came off the set. (Letterman later apologized.)

“The way that I was treated—myself, Britney [Spears], Lindsay [Lohan], all of us—it was a sport,” Hilton says of the trio infamously featured on a 2006 New York Post cover above the headline “Bimbo Summit.” “We were just young girls discovering life, going out to a party. And we were villainized for it.” She learned to make herself numb to it, an ability she links back to CEDU’s rap sessions. “We’d spend hours sitting there with everyone verbally abusing every person in the room,” she says. “I was used to it.”

When the journalist Vanessa Grigoriadis spent a night out clubbing with Hilton for a 2003 Rolling Stone feature, she noticed that Hilton seemed “desperate for respect” and that she had an “odd defensiveness.” “People have this preconceived notion of me that is not who I am,” a 22-year-old Hilton told her. “I’m smart, I’m sweet, I’m nice. I’m a good person.”

Twenty years later, her story fully told, she’s finally enjoying a version of that respect. There is an obvious relief in Hilton’s demeanor and interactions with the world, a deep pleasure in being taken seriously—and actually listened to—for the first time.

“I feel so proud of the woman that I’ve become, because for so long I kept all of that with me,” she says. “All the negative, horrible words that they would say to me every single day, that sticks with you. I just was not secure. Now I feel that people finally respect me and get me in ways that they never did.”

“The way that I was treated—MYSELF, BRITNEY, LINDSAY, all of us—IT WAS A SPORT.”

There is a convenient side to the latest reinvention too. In 2005, the contents of a storage unit she’d used during a move were sold at auction, and a couple of years later, video of an apparently intoxicated 20-year-old Hilton using racial and gay slurs ended up online. When I ask her about it, the story comes back around to her traumatic time in isolation. “Yeah, I’m mortified,” she says. “But after talking to other survivors, I see that so many of the things that I did are classic signs of survival. Everyone lives and learns in life.” In Paris, she writes that in the attack-therapy sessions, “people went for the most obvious target in the ugliest possible language. The N-word. The C-word. The F-word. (Not that F-word, the worse one.) … I don’t remember half the stuff people say I said when I was being a blacked-out idiot, but I’m not denying it.” She further dispenses with a number of her other cataloged mistakes—including a new one, that she didn’t vote in the 2016 election: “Am I standing by these choices? Would I make the same choices again, knowing what I know now? Of course not!”

Hilton says the documentary “changed my entire life” and enabled her to settle down, get married, and start a family: “I never would’ve let those walls down.” She met Reum at a family friend’s Thanksgiving gathering on Long Island in 2019. He was different from her usual type. “He’s not famous. He’s smart. He comes from a nice family. He’s a good person,” she says. “It was the opposite of what I had been used to when I was looking for guys.”

Beginning in her 20s, Hilton had started to think of herself, privately, as asexual. She was romantically linked with a different celebrity every week, but she says her roundly awful sexual experiences—in addition to a sex tape released against her will in 2004, she writes in Paris about being targeted and groomed by a male teacher in middle school—made her something of a prude. “I was known as a sex symbol, but anything sexual terrified me,” she says. “I called myself the ‘kissing bandit’ because I only liked to make out. A lot of my relationships didn’t work out because of that.”

With Reum, she found a new kind of trust. “It wasn’t until Carter that I finally am not that way,” she says, adding with a laugh, “I enjoy hooking up with my husband.”

They fell in love quickly, moved in together during the pandemic, and were married in November 2021. (Their relationship was featured in the Peacock series Paris in Love, which will return for a second season.) “I just feel like after all the hell I’ve been through, I’m finally getting what I deserve, which is someone I can trust and someone to build a real life with,” Hilton says.

In motherhood, she claims she is beginning to slow down—“I’m more interested in babies than billions,” she says, dropping into the voice yet again—but in the weeks after we first speak, she DJs her mom’s annual Christmas party, releases a new version of “Stars Are Blind,” and performs onstage with Miley Cyrus on NBC’s New Year’s Eve special. She has big plans for the metaverse too: In addition to perfecting an AI deepfake, she has developed something called Paris World on Roblox, where she hosts DJ events and perfume launches.

In the interim, she is relishing being a mother and taking in real-world moments that feel new to her—or to the latest version of herself. For a long time, people would approach her for a selfie and want her to say “That’s hot.” These days, she says, “it’s always something about ‘I love what you’re doing for children.’ Or ‘I went through the same thing.’ ” She says hearing other survivors’ stories has proved to be “some of the most gratifying moments in my life.”

“It’s a good feeling to be real,” she continues. “To not feel like some cartoon character all the time. It’s a really good feeling.”