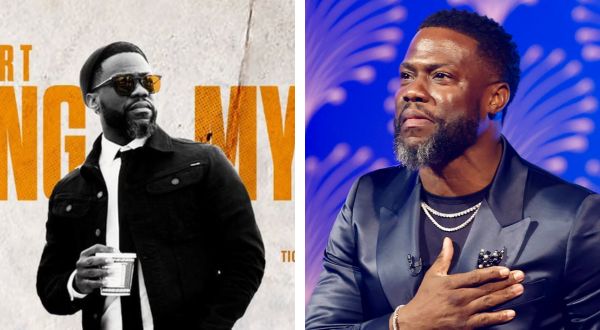

Why did people put up with the hip-hop icon’s anti-Blackness, misogyny and antisemitic “free thinking” for so long?

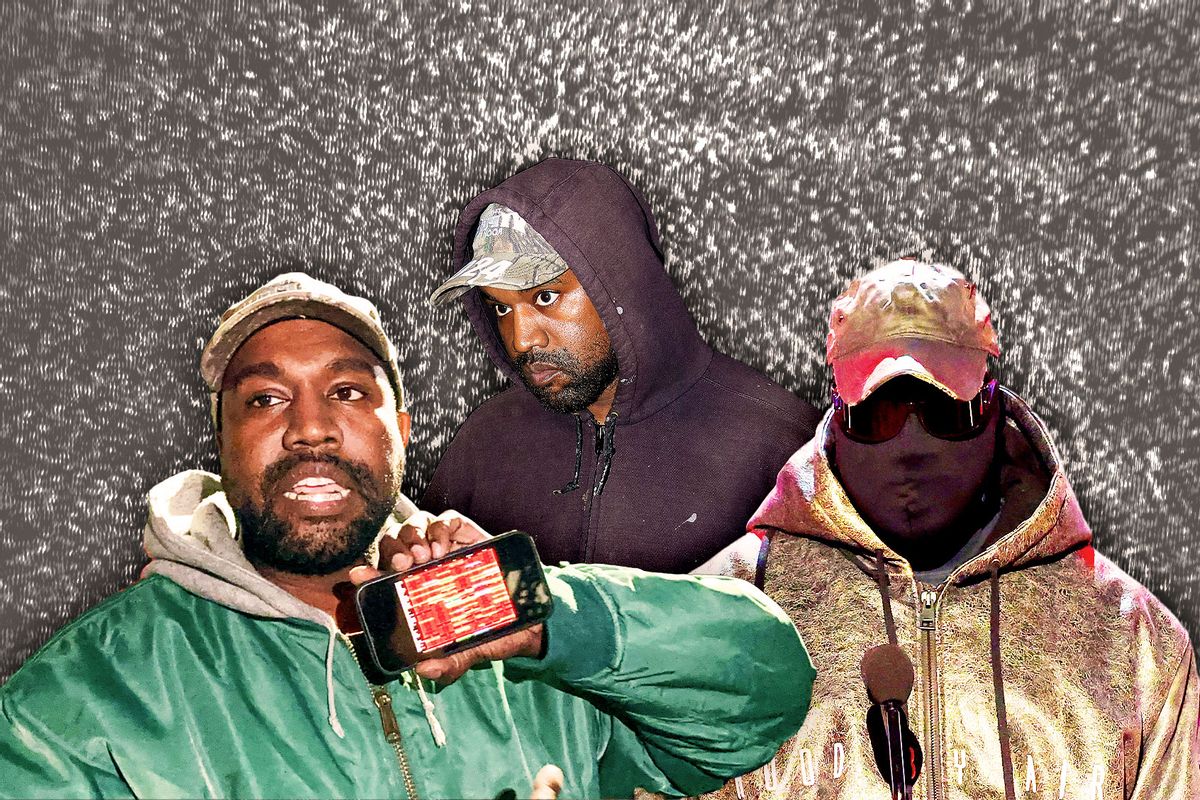

Kanye West (Photo illustration by Salon/Getty Images)Facebook15TwitterRedditEmailsave

Kanye West (Photo illustration by Salon/Getty Images)Facebook15TwitterRedditEmailsave

Typing some version of the term “I’m done with Kanye West” into the search engine of your choice yields an array of results that illuminate as much about who we are as they do about him.

First, we get the usual suspects: links to essays published in major publications in which the author announces they’ve officially pulled the stop request cord on this bus, ding!

These join the smattering of fan departure announcements posted on Reddit, TikTok, YouTube, and other platforms, along with reports that Pusha T, formerly the head of West’s recording label G.O.O.D. Music, is done with him, as is Kid Cudi, Eve, West’s ex-wife Kim Kardashian and, one presumes, Pete Davidson.

Scroll down further to encounter a few posts and stories in which the authors admit they are not quite done with him, but reaching their limit. Those are especially instructive. As Touré explained in an essay for The Daily Beast, he’s had to forgive a lot to remain West’s fan because “bizarre is normal in Kanye’s world.”

So although seeing West pose with Donald Trump in 2016 hurt the writer, “I gave the brother a pass,” Toure said. “I mean, he’s made so much great music.” One imagines West’s stans responding to this with, “So say we all.”

Democracy in the 2010s, aka the decline of Kanye West-ern civilization

Now take a look at the dates associated with these departure announcements, and you’ll notice they’ve been rolling out for a very long time. This Kanye fan let him go in April of this year. This one parted ways with him in 2018 after his unhinged visit with Donald Trump in the White House where he retracted his diagnosis that he was bipolar. This person said “Off, please” in 2021. And this former fan dumped him with extreme prejudice in 2016.

I am struggling to remember whether any other living celebrity has received as much forbearance and faith as this man has.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24103995/1429788074.jpg)

Why everything scares Judith Light, except for aging: “These are the crone years”Keep WatchingAdvertisement:

That Touré essay was written in 2018 too, beyond the point at which Trump had demonized immigrants and residents of major metropolitan areas, with West’s birthplace of Chicago being his favorite scapegoat, and long after the chemical trails behind West’s tweet of “I love the way Candace Owens thinks” dissipated.

“Ye’s making it harder to keep justifying him but for now, I still do,” Touré wrote. “Because I still don’t believe that he really believes any of that conservative stuff. But then again, I don’t believe Owens really believes that stuff either.”

Despite how this looks, I’m not trying to shame another writer for presenting a take that aged like raw fish left out. No, the reason this piece and the many others about West are worth contemplating is that they help make sense of why it’s taken this long for West to become persona non grata in the eyes of most of the public.

Indeed, I am struggling to remember whether any other living celebrity has received as much forbearance and faith as this man has.

“I mean, he’s made so much great music.” Can that truly be all there is? Yes, and emphatically no, of course not. West has proven his ability to produce incredible art, the type that wins a generation’s faith. Consult an industry expert, and they’d likely cite 2010’s “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” as one of the highest achievements in his music catalog, if not his finest work. West’s faithful are more likely to rhapsodize about the way 2004’s “The College Dropout” changed the pattern of their brainwaves. This is the difference between those who can appreciate West with a degree of separation from the emotions attached to him and the people who once testified that the artist’s lyrics and beats spoke to a part of them that may not even have a name or definition.

West music doesn’t vibrate my spirit that way, and I recognize that saying this as a native Chicagoan is heresy to some people. I’d also be lying if I said I never worked it out on the dancefloor to one of his bangers.

But as someone who apprizes great music, who understands how exceptional it is for a Black man to spin his talent into diamonds and platinum, and who has seen how far people will go to excuse the terrible sins of some such men, that explanation completely tracks.

Calling to mind another living celebrity people have forgiven as frequently and easily is a challenge, but one deceased one comes to mind immediately. Michael Jackson endured multiple accusations that he sexually abused young boys while he was alive, even paying a multimillion-dollar settlement to one of his accusers.

HBO’s release of “Leaving Neverland” in 2019 inspired an avalanche of think pieces by critics, and fans, and critics who were fans, wondering how to intellectually square their love and respect for his culturally foundational body of work with what the artist has been accused of doing. This was and is mainly a matter of following one’s moral compass. You’ll notice today that the King of Pop still gets plenty of airplay.

When he died in 2009, author Chris Hedges wrote a damning essay in reaction to the pomp surrounding his funeral, which was broadcast on TV and watched by an estimated 31 million viewers. “A variety show with a coffin,” he called it. However, the target of Hedges’ condemnation was not Jackson, but the celebrity- and media-obsessed culture that propped up his fame despite the allegations that followed him – mainly because his music was just that good.

The cult of self, which Jackson embodied, dominates our culture. This cult shares within it the classic traits of psychopaths: superficial charm, grandiosity and self-importance; a need for constant stimulation, a penchant for lying, deception and manipulation; and the incapacity for remorse or guilt. . . . This is also the ethic promoted by corporations. It is the ethic of unfettered capitalism. It is the misguided belief that personal style and personal advancement, mistaken for individualism, are the same as democratic equality. It is the celebration of image over substance.

It’s never just about the music. It’s about what the artist symbolizes. Like Jackson, West is a Black man who wasn’t born into wealth, didn’t earn a college degree and became a billionaire. For a time. His industry peers’ lack of belief in West’s talent and his nonstop hustle to catch a break are central to his legend, and the reason he inspires young artists.

From there he surfed the age during which the masses were into believing that massive wealth is an indicator that those who hold it know far more than those who don’t; that they are intellectually superior and creatively dexterous; that their outrageous behavior is part of some genius scheme they’ve concocted we don’t yet understand.

It’s never just about the music. It’s about what the artist symbolizes.

When West broke into the white mainstream with his polo shirts and backpacks, he looked safe but wasn’t, and this refers to what people believed to be his politics. The performer wore the preppy uniform believably enough to stand beside Mike Myers in 2005 and stop the world for a moment by declaring on live TV, “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.”

Remembering that incarnation of the man he once was feeds the logic of those who may yet seek reasons to keep defending him. It’s the reason Netflix’s “Jeen-Yus: A Kanye Trilogy” registers in the memory as having come out in another lifetime when in fact it was released earlier this year. The bulk of conversations around that documentary series didn’t concern its success as an account of his career but its potency as a reminder of who he used to be.

If “Jeen-Yuhs” is in the eye of the beholder, this film doesn’t adequately explain Kanye West’s

Corporate America didn’t twist itself into such knots over his transformation from an icon of bleeding-edge style into a tacky cap-wearing MAGA devotee. His Yeezy brand partnerships with Balenciaga, the Gap and Adidas persisted after he went on TMZ and said “slavery was a choice.”

TMZ was comfortable airing that in 2018 but edited out his praise of Hitler. Turns out we only had to wait for a few years. Once West blasted his antisemitic views across social media in October, following that up with visits to Tucker Carlson and Alex Jones, those brands peeled away from him. Creative Artists Agency cut ties with him, Def Jam Recordings dropped his label, and a planned documentary from MRC was shelved. West celebrated by gliding into Mar-a-Lago to dine with Trump and white nationalist Nick Fuentes.

Then, as a post-script answering any who may still believe these are all part of some magnificent stunt or an extended manic episode, Rolling Stone published a Dec. 24 story citing multiple industry sources alleging that West’s Nazi fixation surfaced as far back as 2003 and has frequently come up in conversations with members of his inner circle ever since.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Maybe you’re done with Kanye. Maybe you hadn’t clasped him to your heart in the first place. Hopefully most people recognize that a man whose October tweet inspired Nazi-saluting white supremacists to display a banner reading “Kanye Was Right About the Jews” on an LA freeway is morally indefensible.

An encouraging outgrowth of taking in all of these headlines and contending with the psychic battery they create is that they’re forcing former fans and tastemakers to assess the role culture played in creating him. One such analysis and perhaps the most thoughtful yet, recently took place between Wesley Morris and J Wortham on the New York Times podcast “Still Processing.”

Their conversation engages with what Wortham calls a “cultural complacency and our role in helping create this social monster that we have today.” As she points out, West had a long history of promoting misogyny in his lyrics (“Gold Digger,” anybody?) and making corrosive statements about vulnerable communities, all in the name of being a “free thinker.”

“All that alleged free thinking just winds up doing more harm to people — Black people, Jews, I mean, all people,” Morris points out.

The question now becomes, what does being done with Kanye effectively look like? Not listening to his music isn’t enough. De-platforming him from major social media streams can only do so much. At least his bid to buy the extremist-friendly social media site Parler fell through.

Kanye West still walks among us, turns up in memes and appears on shows popular with right-wing America. The harm he’s causing doesn’t lack evidence and is an ongoing concern. It doesn’t merely endanger a few people behind closed doors but is emboldening untold numbers of malevolent people. What does it mean to truly be “done with Kanye”? I don’t have a definitive answer to that question. I’m not sure who does.

Source: https://www.salon.com/