The ancient man-made subterranean catacombs of Malta, make up an artificial tunnel system first built in prehistoric times. This vast network of tunnels connects temples, dwellings, sanctuaries and ancient rock-cut graves for the dead, all carved underground out of solid stone. While catacombs are prevalent throughout the Mediterranean world, the Maltese catacombs include a unique characteristic which isn’t found anywhere else. Known as agape tables or triclinia, these unusual elements have been the subject of archaeological debate for decades.

Subterranean Mazes and Catacombs of Ancient Rome

Important settlements of the Roman world were riddled with underground mazes which housed the dead in rock-cut graves. Known as catacombs, these collective tombs date to the early Christian era and were usually created just outside the city limits. Pagan and Jewish communities also made use of these types of burials.

Many of these catacombs were decorated with painted frescos and carvings, some with more ornate features than others. In fact, some catacombs have the earliest examples of Christian art, often confusingly mixed with pagan mythological scenes. The complexity of these subterranean passageways makes for a rather daunting meander. For example, the Catacomb of Callixtus in Rome covers an astounding 20 kilometers (12.4 mi), goes down 25 meters (82 ft) and would have held approximately half a million bodies.

Not all catacombs are publicly accessible and many have been lost over time, but those that are give an incredible insight into the burial rites of Roman times. As well as being the final resting place of the populous, Popes, Christian martyrs and saintly relics were also interred in them. Whilst practical considerations such as growing cities probably led to their creation, there’s still something eerie and foreboding about such extensive, dark and complicated monuments to death.

Understanding the Palaeo-Christian Maltese Catacombs

Malta has many catacombs, the most famous of which are the St. Paul’s Catacombs dating to the late Roman period. Many of the Maltese catacombs are in rural locations, but several of them, such as St. Paul’s Catacombs, were part of the ancient Roman city of Melite and were located outside the former boundary ditch in keeping with the laws and customs of that time.

The Maltese catacombs share many characteristics with others in the Roman world, but are much smaller. St. Paul’s Catacombs in Rabat cover around 2,000 square meters (21,528 ft sq) and have the usual rabbit warren of tunnels and rock-cut graves. Just as in Rome, the Maltese catacombs were used by Christian, Jewish and pagan populations. This has been determined by the art and inscriptions found inside them such as carvings of a menorah.

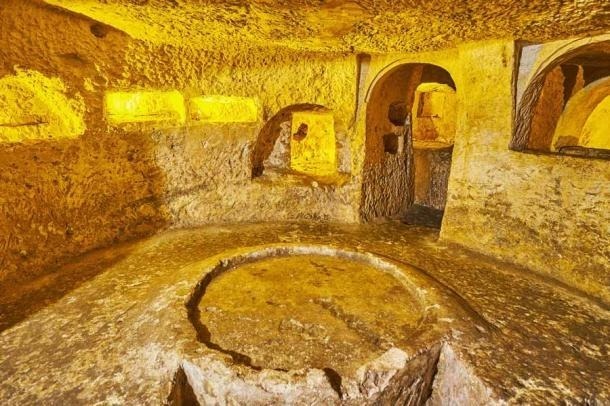

But what isn’t so well known is that they have a feature that is unique to Malta. The first time a visitor to St. Paul’s Catacombs will see this peculiar object is when they descend into one of the largest hypogea. Aside from the expected tombs cut into the walls and floor of a large hall, they will come across two circular tables carved out of limestone facing each other.

Referred to as agape tables or triclinia, experts are of the opinion that they were for funerary feasts, especially since they are surrounded by a c-shaped sloping bench which is thought to resemble the dining areas of Roman houses. What’s strange though, is that they do not really have counterparts abroad.

The Agape Tables of Maltese Catacombs

The triclinia are made up of circular rock-cut tables enclosed by a rim. They vary in width and height. Two thirds of each table is surrounded by a semi-circular sloping area, thought to be seating, also hewn from the rock. This leaves a section of the table open to the room which has no seat around it. It is on this open side that the rim is almost always interrupted by a gap carved into it.

Below this gap, in quite a few cases, a concave channel is cut into the side of the table, which runs from the top of it to the floor. The gap in the rim and the concave channel look as though their function was to drain a liquid. In some tables a circular hole can be seen in the center but it’s not clear where this leads to.

Nearly all the catacombs in Malta have at least one triclinium, no matter whether they are rural, urban, large or small. Experts therefore believe that these unusual features must have played an important role in funerary rituals of the late Roman period. Bizarrely, some of the sloping benches are too small to have been used as seats. It’s thought these may have had a symbolic use instead.

Some of the tables are broken in areas which may have been due to later reuse or remodeling of the burial chamber but nothing is certain. Although the St. Paul’s Catacombs are the most extensive and famous with a large visitor center, there are many others throughout the islands, nearly all of which have triclinia. A few are easily accessible, others can be viewed on certain open days, but some are sealed for future preservation.

The Saint Paul’s Catacombs in in Rabat, Malta. (Hnapel / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Did the Agape Tables Serve a Feasting Function in Maltese Catacombs?

The idea of the Maltese triclinia having had a feasting function is related to their similarity to domestic dining furniture from Roman times and the fact that the refrigerium, a pagan and then Christian funerary feast, is well attested in literature of the period.

The furniture belonging to domestic dining rooms of villas had several incarnations during its time. The earliest examples consisted of rectangular tables surrounded on three sides by long benches called lecti. However, these evolved into semi-circular seating areas and round tables. It’s these later dining rooms that look very similar to the triclinia of the Maltese catacombs.

An example of this can be seen in a depiction of the Last Supper at the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna and in the center of the floor mosaic in the Little Hunt Room at the Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily. A connection with funerary feasts is alluded to in three of the catacombs of Rome. Frescos in the Catacombs of Priscilla, Callixtus and Peter and Marcellinus in Rome show diners sat on a semi-circular bench with round tables in front of them. These are commonly thought to represent funerary feasts and the style of seating is reminiscent of the Maltese catacombs.

However, none of the catacombs in Rome have rock-hewn tables and benches like those shown in the frescos. Neither do those in Naples or Syracuse. Another problem with these depictions is that none of them show the break in the rim or the concave depression that are common features of the Maltese catacombs. The researchers Camilleri and Gingell LittleJohn noticed that the Casa del Moralista in Pompeii does have an indentation in the front of the square dining table. Once again though, this is a domestic villa so it’s difficult to draw conclusions about the triclinia in the catacombs.

An obvious square-shaped triclinium can be seen in the Kom el Shogafa hypogeum in Alexandria. This particular catacomb shows a mix of Hellenistic, Egyptian and Roman styles and the triclinium is identical to that found in Roman villas. Sidret el-Balik in Libya is a catacomb with semi-circular benches surrounding stone tables. It’s probably the closest in appearance to the Maltese triclinia but both Kom el Shogafa and Sidret el-Balik still lack the exact same features including the “drainage” channel.

Agape table at the St. Cataldus Catacombs in Rabat, Malta. ( efesenko / Adobe Stock)

Commemoration and Cleaning at the Agape Tables

If the triclinia were used for feasts, then it’s debatable as to whether they were for funerary rituals after a particular burial or were annual events to commemorate all of the dead. One theory as to why the tables appear to have drainage channels is that it was to make them easier to clean. However, in domestic triclinia this would surely have been a useful feature too except there seem to be only a couple of examples of it.

Perhaps they had a role that’s indigenous to the islands and has been entirely misunderstood. After all it was a time when the local Maltese population would have still continued their own traditions and customs mixed with Roman influence. In reality, aside from the tables and benches being circular, there’s nothing else that really connects them to the feasting frescos of the Roman period such as literary references.

In the San Giovanni Catacombs outside of Syracuse in Italy, feasts to the dead took place by feeding the corpse milk and honey poured through three holes in a slab covering the grave, a symbolic ritual. Once again, no funerary tables or couches existed there for the living to celebrate the dead in the way they appear in Malta.

Strangely, the exedra, which is the name given to the walled area surrounding the table and bench, often has graves cut into it. This would mean the diners feasted with bodies or skeletons at very close proximity, especially where the seating areas are small which doesn’t seem terribly practical. At Kom el Shogafa in Alexandria, although the feasting area is in the catacomb, it’s in a separate area to the burials.

Art of the Maltese Catacombs

Although the Maltese catacombs do not have the ornate frescos of those in Rome, perhaps something can be learned from the carvings and art that have been discovered in them. Doves, floral arrangements and the Chi-Rho symbol are fairly common motifs. The three Tal-Mintna hypogea discovered in the small village of Mqabba have scallop shell decorations and carved pilasters. On the back wall of the triclinium they also have eight pyramid-shaped holes. It’s not known what these represented and they are quite rare but may have been for oil lamps .

The Ħal Resqun catacombs, which are preserved under a traffic roundabout and not publicly accessible, are unusual for their human, animal and bird figures carved in low relief, along with detailed fluted pillars. Ħal Resqun is a much clearer example of Christian iconography than many of the other catacombs.

The same can be said of the Salina Catacombs which have carvings of palm fronds, spirals and crosses. The Maltese catacombs can perhaps be seen as representing a transition period between pagan and Christian beliefs but there are certainly no funerary feasts depicted in any of the carvings and paintings that have been found.

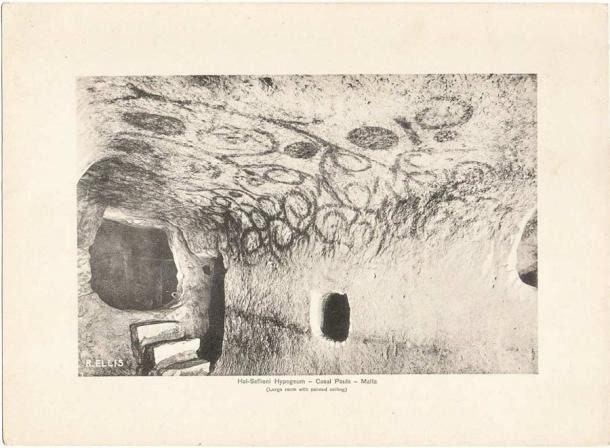

Image of a large rock-cut room with painted ceiling at Hal Saflieni Hypogeum taken by Richaed Ellis circa 1900. ( Public domain )

Underground Landscape of the Palaeo-Christian Catacombs

Malta is well-known for its tunnels and caves. Since the islands are predominantly made up of two types of limestone, there are lots of natural cavities caused by erosion which have been expanded in the past to create troglodyte dwellings and tombs. As with many places in the southern Mediterranean, rock-cut graves have been a feature of the landscape since the Neolithic with palaeo-Christian catacombs being the most recent incarnations.

The Neolithic also saw the introduction of complex hypogea contemporary with the megalithic temples which may have had a dual function as burial grounds and ritual sanctuaries. During the Early Modern Period, the construction of the capital city of Valletta by the Knights of Malta saw the excavation of a web of underground tunnels for storage and drainage. In more recent times, WWII shelters were dug in many towns and villages.

Because of the sheer number of underground complexes, strange rumors about subterranean Malta have a long history. One famous rumor is that Malta has tunnels running the full length and breadth of the islands, although these were boarded up during the British period for health and safety reasons. Another creepy legend is about disappearing school children in the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum , implying that this fully excavated monument is not fully excavated at all, but extends its reach far beyond the town of Paola.

What’s certain is that the palaeo-Christian catacombs were in use during the fundamental transition period between Punic and Roman Malta, a time when cultural influences from different parts of the Mediterranean were all felt on these small islands. That Malta developed its own consistent style and unique features throughout the many Maltese catacombs should not come as a surprise. If only it was possible to travel back in time and see what exactly was happening in these fascinating ritual feasts.

Sources:atlasobscura.com