Recent observations by the James Webb Space Telescope show that the planet has a sweltering dayside temperature of some 450 degrees Fahrenheit (232 degrees Celsius).

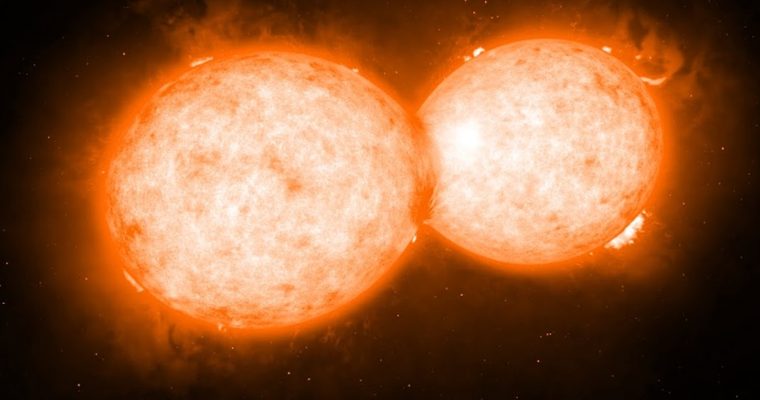

Trappist-1 is an intriguing system that consists of a red dwarf star tightly orbited by at least seven rocky exoplanets. New research, made possible by the James Webb Space Telescope, shows that the innermost planet, TRAPPIST-1 b, is likely too hot to host any atmosphere at all.NASA/JPL-Caltech

The TRAPPIST-1 star system, located some 40 light-years away, hosts at least seven Earth-like exoplanets. But new measurements taken by the James Webb Space Telescope’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) show at least one of those rocky planets is likely too hot to host an atmosphere.

That doesn’t bode well for any hopes that the world might harbor life. However, despite the news that this planet appears inhospitable, the new observations still serve as a major achievement.

“There was one target that I dreamed of having. And it was this one,” said study co-author Pierre-Olivier Lagage of the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), who spent more than two decades developing MIRI, in an ESA release. “This is the first time we can detect the emission from a rocky, temperate planet. It’s a really important step in the story of discovering exoplanets.”

The new research was published today (March 27) in the journal Nature.

A closer look at TRAPPIST-1’s closest planet

The exoplanet in question, TRAPPIST-1 b, is the innermost world in the TRAPPIST-1 star system, which astronomers discovered hosts more than a half-dozen rocky planets in early 2017. TRAPPIST-1 b is some 1.4 times as massive as Earth. But unlike Earth, it orbits a star much smaller than the Sun.

The red dwarf star TRAPPIST-1 hosts seven known exoplanets, and all of them could easily fit inside the orbit of Mercury.NASA/JPL-Caltech

The star TRAPPIST-1, first discovered in 1999, is an ultracool red dwarf (or M dwarf). These are the most common type of star in the Milky Way, and, presumably, the universe. Due to their diminutive size, such stars put out much less energy than stars like the Sun. But red dwarfs are also known to sport strong stellar winds and violent flares, which has raised questions about how likely it is for planets around them to be hospitable to life.

“There are ten times as many [red dwarfs] in the Milky Way as there are stars like the Sun, and they are twice as likely to have rocky planets as stars like the Sun,” said Thomas Greene, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Ames Research Center and lead author of the study. “But they are also very active — they are very bright when they’re young, and they give off flares and X-rays that can wipe out an atmosphere.”

Previous observations of TRAPPIST-1 b taken by both the Hubble Space Telescope and the Spitzer Space Telescope found no evidence of a puffy atmosphere around the world. But these observations also couldn’t rule out the possibility that the planet was cloaked in a dense, thinner one.

One way to shed more light on whether TRAPPIST-1 b has an atmosphere or not is to measure the planet’s temperature. “This planet is tidally locked, with one side facing the star at all times and the other in permanent darkness,” said Lagage. “If it has an atmosphere to circulate and redistribute the heat, the dayside will be cooler than if there is no atmosphere.”

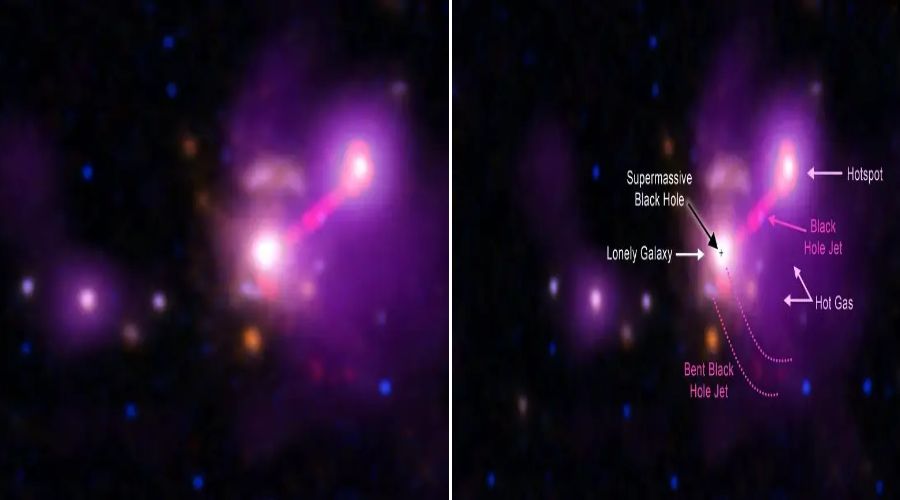

This graph plots the combined data from five separate observations made by the James Webb Space Telescope’s MIRI instrument. These are the first observations of the thermal emissions of TRAPPIST-1 b — or any other rocky and relatively cool planet that’s as small as Earth.NASA, ESA, CSA, J. Olmsted (STScI), T. P. Greene (NASA Ames), T. Bell (BAERI), E. Ducrot (CEA), P. Lagage (CEA)

Researchers achieved this by watching as TRAPPIST-1 b moved behind its host star, a technique called secondary eclipse photometry. By subtracting the brightness of the red dwarf alone from the overall brightness of the star and planet combined, researchers were able to determine how much infrared light (or heat) the planet emits. That’s no small feat considering the system’s star is some 1,000 times brighter than the planet, resulting in a brightness change of less than 0.1 percent.

They calculated that TRAPPIST-1 b has a temperature of around 450 degrees Fahrenheit (232 degrees Celsius).

“We compared the results to computer models showing what the temperature should be in different scenarios,” said co-author Elsa Ducrot of CEA. “The results are almost perfectly consistent with a blackbody made of bare rock and no atmosphere to circulate the heat. We also didn’t see any signs of light being absorbed by carbon dioxide, which would be apparent in these measurements.”

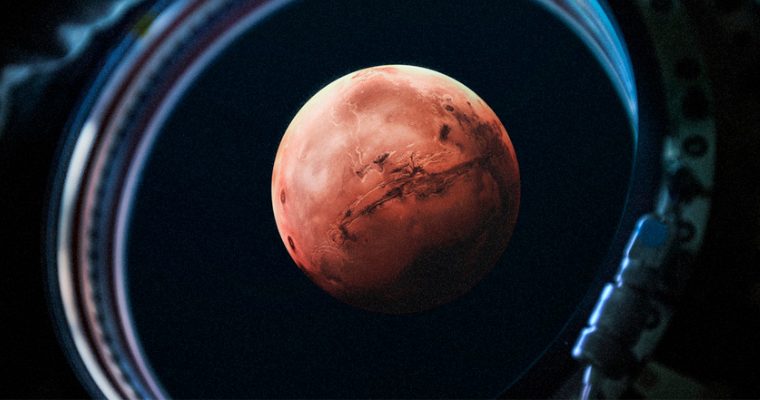

Despite how close it sits to its star, the surface of the exoplanet TRAPPIST-1 b is not nearly as scorching as Mercury. But it still appears to be too hot to host life.ILLUSTRATION: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI); SCIENCE: Thomas P. Greene (NASA Ames), Taylor Bell (BAERI), Elsa Ducrot (CEA), Pierre-Olivier Lagage (CEA)

To confirm that TRAPPIST-1 b really lacks an atmosphere, researchers are now working to obtain additional secondary observations using James Webb’s MIRI instrument. With the goal of obtaining a complete phase curve that shows how TRAPPIST-1 b’s brightness changes over the course of its entire orbit, researchers are optimistic they’ll soon know beyond a doubt whether the world has an atmosphere or not.

“It’s easier to characterize terrestrial planets around smaller, cooler stars,” added Ducrot. “If we want to understand habitability around M stars, the TRAPPIST-1 system is a great laboratory. These are the best targets we have for looking at the atmospheres of rocky planets.”